Hellish backpack getaway: Fear, loathing, and vertigo on Oregon's Illinois River Trail 1161

Back in the summer of 2002, as a reporter for The Oregonian newspaper, I covered the Biscuit Fire, which burned through nearly 500,000 acres of government managed timberland in southwestern Oregon. I recall standing on a remote road high above the action, watching magnificent flames rise from a summertime tinderbox called the Kalmiopsis Wilderness.

Helicopters lifted huge buckets of water out of the emerald green Illinois River and dropped them on a carpet of towering conifers, which to me looked about as good as throwing thimbles of water at a car fire. From where I stood, the suppression efforts only incited the wildfire. Every now and then, orange flames bellowed out of the jagged hillsides straddling the river, a powerful reminder that Mother Nature really is a mad scientist.

“I promised myself I’d return to the wild Kalmiopsis …”

Photo by Steven Nehl, The Oregonian

I promised myself I’d return to the wild Kalmiopsis to see how it fared after the largest North American wildfire of 2002.

It would take fifteen years.

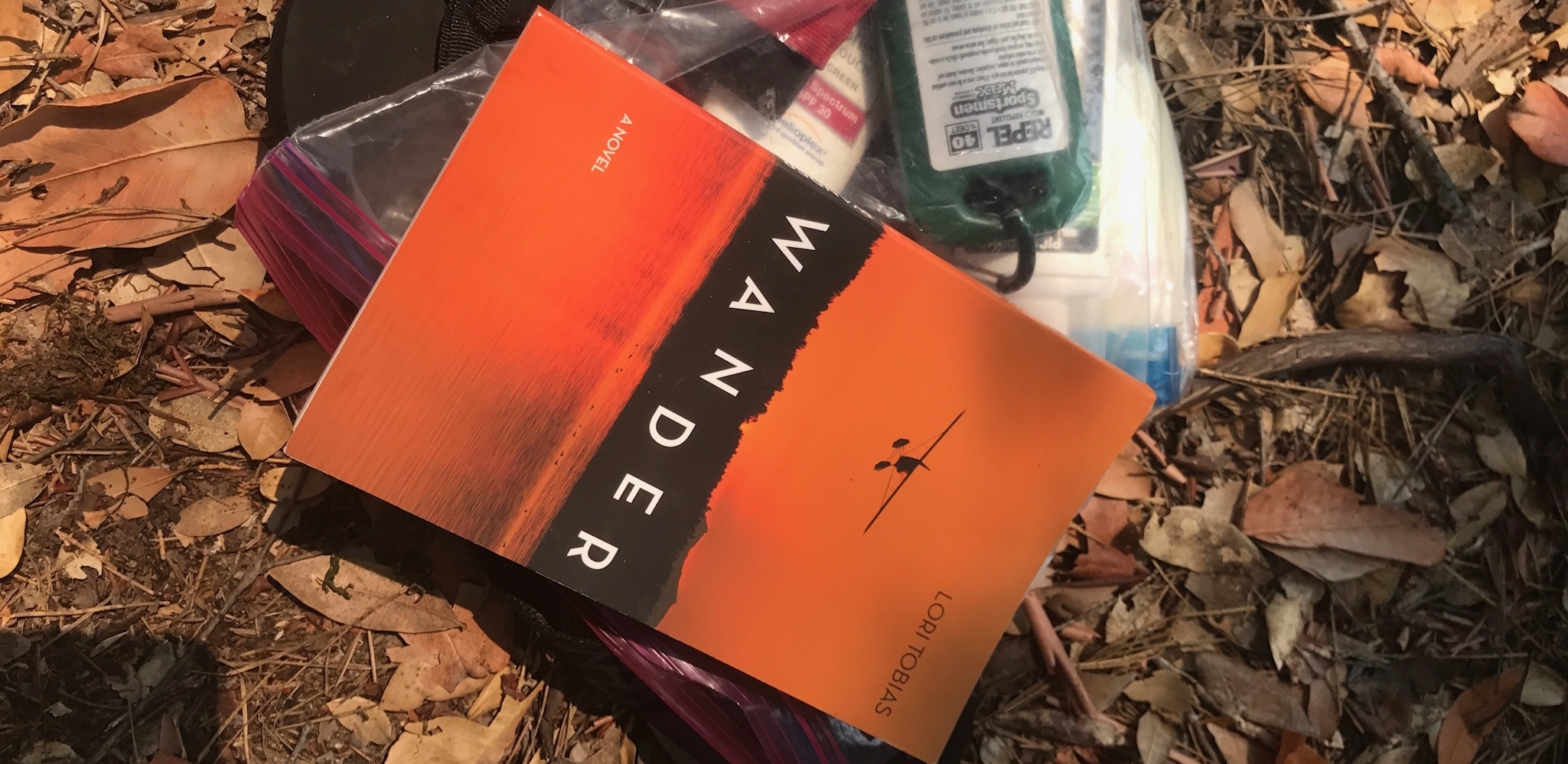

On Saturday, August 5, 2017, my girlfriend Kristin and I drove to Selma, Oregon, on our way to a remote spot called Briggs Creek, on the eastern side of the Kalmiopsis. Our plan was to park there and hike from the Illinois River Trail to a remote campsite six miles into the wilderness, where we would pitch camp, swim, read books, decompress, and hike out Monday morning.

But a wildfire, one of several burning in southern Oregon, would interrupt our plans.

We made the 19-mile-drive from Selma to Briggs Creek, much of it a harrowing ride over a twisting single-lane gravel road cut into steep hillsides. I must acknowledge I’m a weenie when it comes to heights, a panicky we’re-all-gonna-die kinda guy. But seriously, it was easy to imagine some weekend drunk rounding a corner on two wheels and punching us over a sheer cliff.

The last mile or two into Briggs Creek was a lot of fun because Kristin got to try out all the features of her 2016 full-size Range Rover SUV, “Midnight.” She bought the vehicle in part so we could take adventures in the wilder, weirder, and woollier reaches of the Pacific Northwest. I secretly believe she bought the car so she could play “Jane Bond” on snowy drives to her favorite skiing spots. It's a cool vehicle, one that’ll climb over boulders, slosh through monstrous mud puddles on three wheels (seriously), and scale improbably steep, slippery, twisting, rutted hillsides. And it will go from 0 to 90 very, very fast.

But we learned it’s not scratch resistant.

Midnight took one for the team.

Yeah, ouch. Nothing that a good buffing won't take out.

Blackberry bushes had their way with the vehicle as we neared Briggs Creek. And, just as a warning, you won’t want to try the final two miles of the dusty, rock-strewn road, which features axel-busting ruts and potholes, in anything resembling a passenger car. You’ll need a vehicle with high clearance and preferably four-wheel drive. Also, as you approach Briggs Creek, you’ll confront a fork in the road. Go left, m’friends. We took a right, which carried us into the stratosphere.

The drive from Selma to the trailhead at Briggs Creek takes about 90 minutes if you drive carefully and don’t know the road, or haven’t taken a wrong turn onto the backwoods set of Deliverance (WARNING: video is graphic, and awful, and will give you nightmares. Click at your own risk). We hit the dusty parking lot well after lunchtime. Southern Oregon, normally dry and hot in the summer, was nearing the end of a hot spell with daytime temps close to 100 and abnormally high humidity.

I’m not a spring chicken and neither is Kristin. We’re more like late-harvest Gewurztraminer, sweet, smooth, and a little too long on the vine. However, for a couple of fifty-somethings, we’re not in terrible shape. On October 2, 2016, we made the summit of Mount Kilimanjaro (19,341 feet), the highest freestanding mountain in the world. So yeah, kids, we got game.

It was stupid hot by the time we reached the 1161 trailhead at Briggs Creek. (When you reach the trailhead, you'll see that it's marked "1162." Disregard. This is, in fact, the eastern trailhead for Trail 1161.) We shouldered our packs and snapped a selfie or three before setting off on what was a pleasant and relatively flat stretch of the trail that ran parallel to the Illinois River. We ran into a couple of nice women from Portland’s Lewis & Clark Law School and chatted for a bit.

They would be the last humans we saw in the Kalmiopsis.

Your faithful correspondent (at left) with Kristin Quinlan.

We ascended a wide, nicely groomed trail along the southern face of Bald Mountain (3,795 feet). As the sun beat down, I began to regret all the great craft beer I drank at the Taprock in Grants Pass the night before. We were heading for the Pine Flat campsite, pouring sweat in the open sunlight.

Soon we hit a stretch of gradual climbs, with steep drop-offs next to the trail. I refused to stop or look down into what Kristin professed were a series of astounding views. Instead, I ostrich-walked past any point at which I would surely fall off the mountain, plummet to my death, and leave a mournful nation.

We stopped for water at a couple of cool creeks before reaching a muggy section of woods. The shade was nice, but the forest was full of bugs, including nasty biting flies and those gnats – or whatever the hell they are –screaming in their little high-pitched gnat voices as they spelunk into your ear canals to lay eggs on your eardrums.

The wilderness is choked with deer and Roosevelt Elk, rattlesnakes and frogs and salamanders, bald eagles and northern spotted owls, and the Illinois River teems with salmon. There’s also tangled blackberry, poison oak, and stretches of dead and charred trees poking out of denuded hillsides like tall, wooden tombstones. Also, black bear.

We reached a crossroads in the woods, where the Illinois River Trail continues west and Trail 1216 drops some 800 feet over the next mile, one of those switchback sections that give your quads fits if you brake too hard. At the bottom of the hill, we reached the Pine Flat campsite only to discover we were all alone – except for a monstrous pile of bear crap purpled by blackberries.

Bear scat. That was a whole lot of blackberries.

We made camp on a hill overlooking a wide stretch of the Illinois River, set up our tent, and headed for a field of large, oblong rocks next to noisy rapids. We explored the river, drank some adult beverages, took a nekkid swim, and fired up the old reliable backpacker’s stove to eat the old reliable Mountain House lasagna.

I had just enough rope, and just enough energy, to hang a very lame bear bag. It dangled sadly about four feet off the ground. A baby bear could have taken it down with one swipe, seated. My contraption should have come with a sign: “Here, bears, eat ye of it. Just don’t nibble on the humans.”

Kristin took one look and busted up.

“It’s more like a bear piñata,” she said.

We slept with the tent flap open and, a few hours after first light, carried our mess kit down to the rocks to make a breakfast of Irish Coffee. Buzzing on Jameson’s, I climbed a big clump of rock that looked like a gigantic nugget of faded gold. There I practiced Mister Miyagi’s famous Crane Technique. (“If do right, no can defense.”)

Your correspondent's fine impersonation of Ralph Macchio.

We forded the river just above the rapids in our flip-flops, carrying lunch and some books. We were halfway across when I blew out my right flip-flop and fell into the water, banging my left shin on a rock, which raised a big knot, and forced me to utter many bad words. We clambered for a meadow on the other side of the river and spread the footprint of our tent in the shade of a scrubby tree.

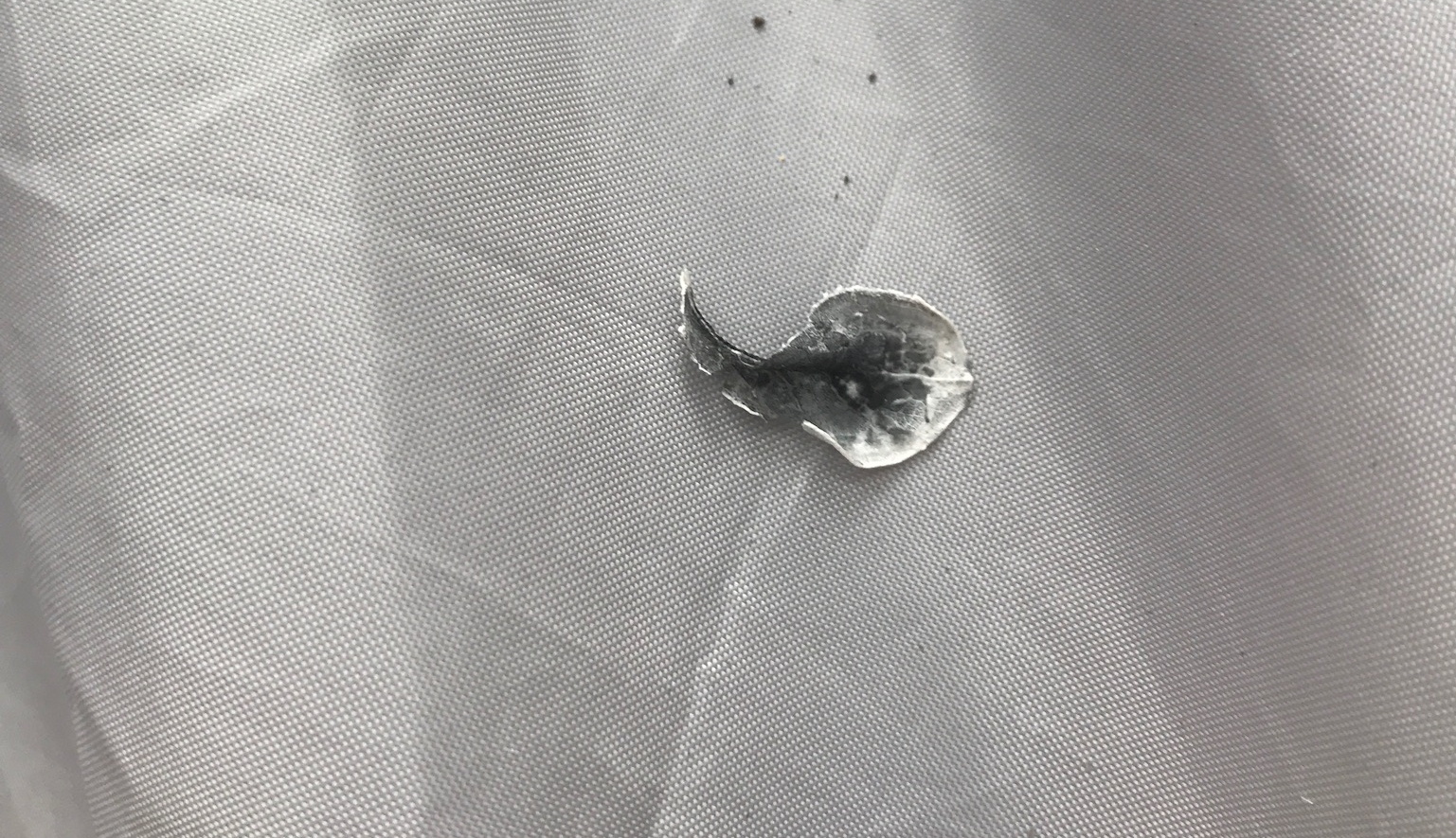

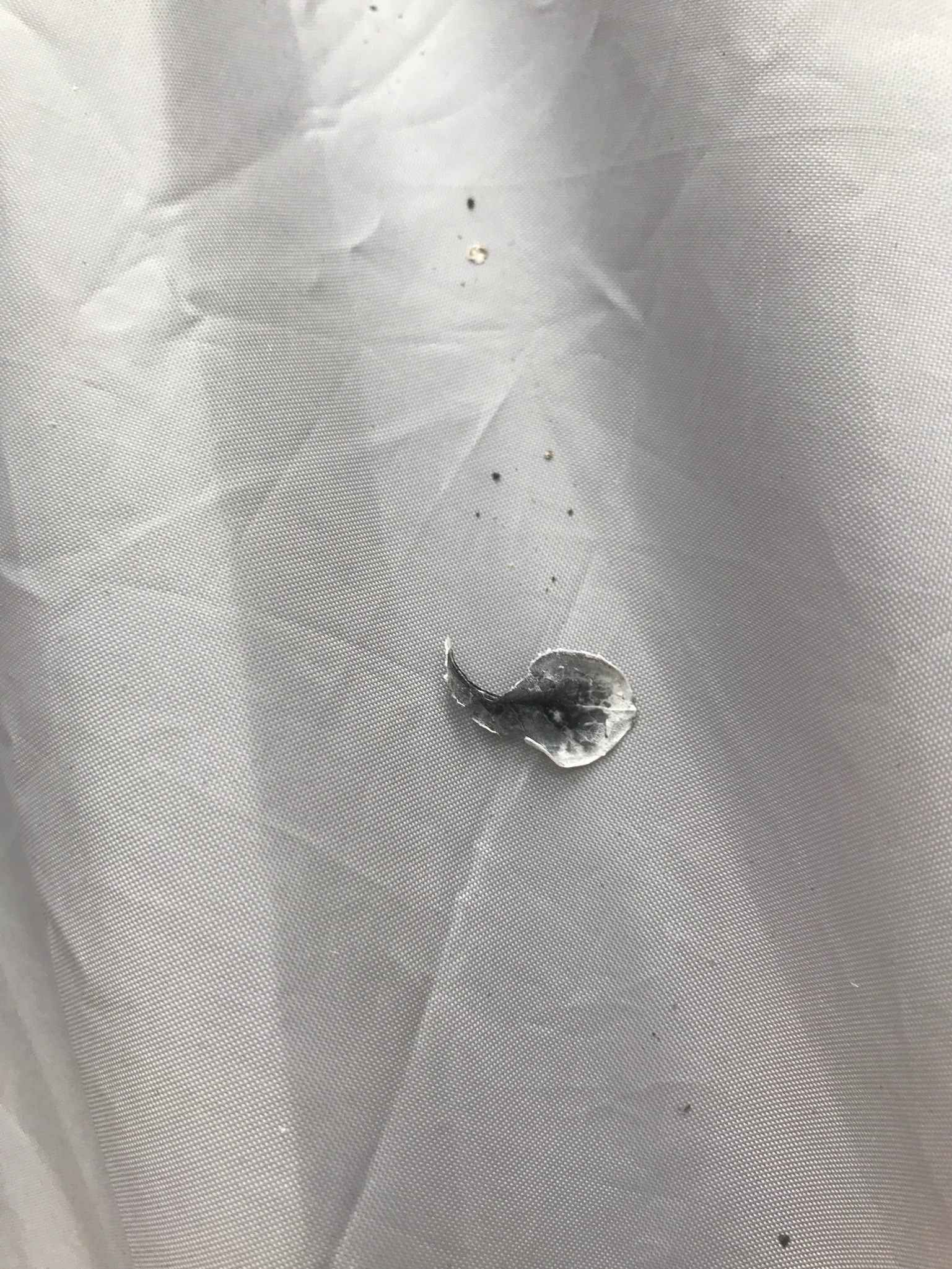

Later, eating Triscuits and cheese, we saw smoke collecting thickly in the mountains. During wildfire season, the haze can carry hundreds of miles. But Kristin now began to notice tiny specks floating to the ground around us, some black, some white. They looked like ashes, she said. I told her it was probably something falling off the nearby hardwoods. But neither of us bought it.

We packed our gear into a stuff-sack and Kristin carried it over the river to the tent as I, your valiant correspondent, equipped with only one working flip-flop, swam to the other side. I found a pool cut into the rock where the water ran green as jade. I was soaking my sore shin, trying to figure out what to do, when Kristin walked up and knelt down with her iPhone. She showed me photos of our tent now speckled with ash. Then a large white flake fluttered down like a moth and Kristin mashed it into her hand, incontrovertible proof that a wildfire had drawn closer than we had imagined.

The trouble was that we had no earthly idea where the fire was. We had no cellular service. Zero bars in the Kalmiopsis. The wind seemed to be coming at us from the southwest. Our options seemed limited to three: 1) Stay put on the open river and hope for the best; 2) Head westward on the Illinois River Trail toward the Rogue River and civilization and hope the fire didn’t jump the river; or 3) Go back the way we came and hope the fire didn’t cut us off.

Kristin and I had been dating more than seven years and had never shared an emergency like this. We talked out our strategy and came to one conclusion. Our happy little campout had come to an abrupt end. Time to bail.

Closeup of ash that fell on tent.

We hiked up to our campsite and hurriedly packed our gear, including the unmolested bear bag. Then we began the steep climb to Trail 1161, deciding we would head back the way we came. Kristin is the toughest woman I know, and I know a lot of tough women. She carried a heavy pack, stopping only when we had to stretch our backs. We were both knackered, running out of electrolytes. But we kept moving.

The sun was brutal, bearing down on us as we made our way to the exposed trail high above the river. We drank from bottles of warm water, peering all around us for signs of smoke. We were going as hard as we could, but we felt like ants crawling across a gymnasium floor.

Kristin grew nauseas, one of the warning signs of heat stroke. About ten minutes later, we stopped at one of the creeks racing down the canyons and poured cool water on our heads, tasting sweat on our tongues. I shook blue, powdered Gatorade into a bottle of the crystalline water and Kristin, who normally hates the stuff, gulped it down. We drank until we couldn’t hold another drop, splashed around until we were fully hydrated, and pushed on.

We reached Briggs Camp after about three and a half hours on the trail, chucked our gear in the dusty Range Rover and got the hell out of the Kalmiopsis.

We didn’t know it at the time, but the temperature had climbed to 100 degrees that afternoon. The ashes we had observed at Pine Flat floated six to eight miles from the Chetco Bar wildfire, where sixty-six firefighters fought a blaze estimated at 4,341 acres. They had failed to contain any part of the fire. Humidity and timid breezes kept it from roaring over the hillsides toward us.

While we had probably been in little danger, we did the smart thing by bugging out.

Kristin and I returned to the Taprock Northwest Grill, which serves some of the region’s best craft beer. The menu lists Budweiser at the bottom with these words: “Ha! Made you look / Not really / Just Kidding/ Ain’t happening.” But after our fretful flight out of the Kalmiopsis, beer wasn’t going to cut it. We needed grownup beverages. Kristin drank vodka sodas. I had rum tonics.

The bartender, God bless his soul, leaned into them.

-- 0 --

UPDATE FOR BACKPACKERS (August 17, 2017): The Chetco Bar fire has grown to 6,500 acres, with strong winds pushing the blaze over the Chetco River on a trajectory for Pine Flat. Trails on the southern side of the Illinois River have been closed by the U.S. Forest Service supervisor.

FINAL UPDATE (November 2, 2017): The Chetco Bar fire, which grew to 191,125 acres, is fully contained.

U.S. Forest Service photo of the Chetco Bar wildfire.